Davide Zucco – Federico Maddalozzo

Anyway, what kind of society is it when you can’t even buy a chair?

Article published on AD Italia on the September 2020 printed issue

This, among others, is a question Donald Judd asked himself in his 1986 essay “On Furniture”, written approximately a decade after producing a wooden bed and a number of stainless steel wash basins for his New York studio, at the beginning of the 70's. For the American artist, who is considered one of the founding fathers of minimalism, much like for the majority of artists who approached the subject, the interest in designing furniture was fuelled by personal necessity. Donald Judd first designed furniture for his New York studio and, some years later, for his children’s bedroom in Marfa, Texas. These experiences had a lasting impact on Judd, and led him to continue in the development of a relatively large series of furniture, which lasted until 1993.

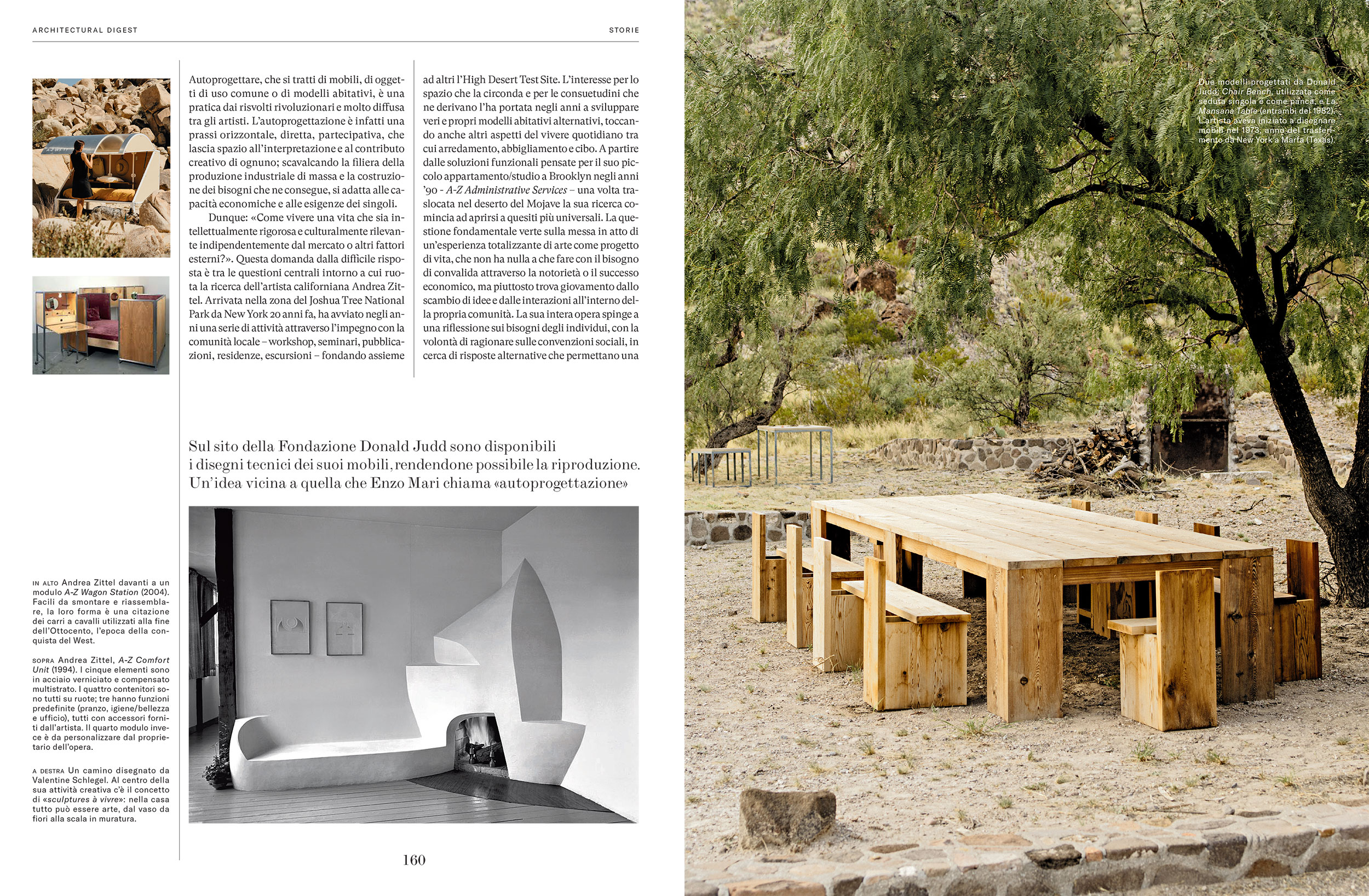

The Donald Judd Foundation – which is responsible for the preservation of various venues between New York and Marfa, such as homes, studios, offices and exhibition spaces that are open to the public – continues to this day to produce his furniture. The pieces are made to order and in faithful observance of their creator’s philosophy. They are assembled following his principles of production (by employing local artisans), quality, distribution and pricing (they are relatively inexpensive, compared to the market value of his art).

Plans and drawings are available on The Foundation’s website, making it possible for those who are interested to reproduce them. A sort of nod to Enzo Mari’s “autoprogettazione”. Mari’s vision, presented in his exhibition at Galleria Milano in 1974 and in the publication that accompanied it, was to share with the community designs and blueprints for the production of furniture “of simple assembly, to be made using wood boards and nails”, making them available to anyone “except factories and traders”.

Self-designing, be it furniture, objects of common use or inhabitable spaces is a revolutionary practice that is widespread among artists. Self-designing is, in fact, a horizontal, direct, participatory practice which gives space to one’s own interpretation and creative contribution. Bypassing the industrial mass-production chain and the consumeristic needs it creates, self-designing adapts to the individual’s economic means, fulfilling their actual needs.

Yet “how can one live a life that is intellectually rigorous and culturally relevant, regardless of the market or other outside factors?”. This question, with its difficult answer, is one of the central issues around which Californian artist Andrea Zittel develops her research. Having moved from New York to the Joshua Tree National Park area twenty years ago, in recent years the artist has embarked on a series of activities focused on her commitment to the local community – workshops, seminars, publications, residencies, excursions – and co-founded the High Desert Test Site.

Andrea Zittel’s interest in her surrounding habitat and the habits that derive from it led her, over the years, to develop alternative habitation models and touch on other aspects of daily life such as interior design, clothing and food. Starting from the functional solutions she developed for her small Brooklyn studio flat in the 1990s – A-Z Administrative Services – her research started to open to more universal questions once she relocated to the Mojave desert. The fundamental question being how to enact a totalling experience of art as life-project that is unaffected by the need to obtain validation through notoriety and economic success, but rather benefits from the exchange of ideas and interactions within the community. Andrea Zittel’s oeuvre prompts a reflection on what might be the needs of the single individual, steering the conversation towards social conventions, looking for alternative solutions that allow for some independence and a level of self-design, in a broader sense.

For artists, building furniture is often the fulfilment of practical needs. Investigating the relationship between sculpture, body and visitor, Franz West’s interest for chairs, sofas and the unusual furniture he creates in his artistic production begins in the studio. In having his picture taken on various occasions in his place of work, posing in contemplation of his artwork while reclining on one of his bizarre functional creations, the artist means to send a message: art can be born out of not working, out of contemplation, out of rest and even boredom. This message, in his exhibitions, becomes an explicit invitation to the public. One of his most spectacular interventions took place in the 1992 edition of Documenta, in Kassel. There, in the parking lot facing the main exhibition venue, Franz West presented the “Auditorium” installation: 72 sofas covered with worn out, discarded Persian rugs, which had been procured making the rounds of Vienna’s dry cleaners, and arranged to provide the public with an area for rest and reflection.

It makes us wonder what might be the difference between his furniture and his sculptures. Referring to an armchair, the artist says: “the perception of art, takes place through the pressure points that develop when you lie on it”. Artwork and interaction, therefore, are one and the same; the artwork can’t be considered without also considering the way in which it will be used.

The work that most defines Valentine Schlegel, realised by the artist in many French residences between the 1960s and 2002, can also be considered as being born out of practical need.

Valentine Schlegel’s fireplaces came from the need to create the perfect exhibition support for her artwork. After seeing one of her vase sculptures placed on the mantelpiece at a friend’s house, she realised that the context didn’t work, and, perhaps rather drastically, she decided to completely redesign the area. From this point onwards her work took the shape of the domestic habitat. Her white plaster fireplaces, which expand into benches and shelves, had little circulation in art galleries and museums, remaining intimately connected to the private spaces for which they were conceived.

Set in a more contemporary context, but with similar poetic intention, is the work of Charlotte Dualè, an artist working predominantly with ceramic who created a series of site-specific interventions, hybrids between artwork and furniture for her Berlin flat. Her kitchen and library, realised with handmade ceramic tiles, are not only functional but also rich in sculptural elements.

The number of artists who, for various reasons, realised elements of furniture – for their studios or homes, as organic elements of their artistic research or exhibition concept – is potentially infinite. The need and possibility of operating outside of mass production and distribution channels, the quality and time dedicated to the making of this kind of furniture, the intimate spaces where these works take shape, and the personal motivations behind them, set self-made furniture apart from purely functional creations, allowing them to blend into the life and the artistic and political vision of those who conceived them. At a time in which our consumer habits have become increasingly unsustainable and, simultaneously, we see an increased need to recognise ourselves in one's own way of home making, the research, experimentation and sensibility these artists contributed to express – and which continues to be put into practice today – seem of particular importance in the reimagining of the relationship between art, design, and ways of inhabiting.